Creativity and Innovation Unchained: Why Copyright Law Must be Updated for the Digital Age by Simplifying It

The authors of this paper argue that “the basics of copyright are fully compatible with modern technology, but specific provisions enacted years ago to try to address long-gone business and technological problems are still on the books. Instead of solving yesterday’s problems, these sticky laws shackle today’s creative marketplace.”

Contributors

Alden Abbott

Adam Mossoff

Kristen Osenga

Brian O’Shaughnessy

Mark Schultz

This paper was the work of multiple authors. No assumption should be made that any or all of the views expressed are held by any individual author. In addition, the views expressed are those of the authors in their personal capacities and not in their official/professional capacities.

To cite this paper: A. Abbott, et. al., “Creativity and Innovation Unchained: Why Copyright Law Must be Updated for the Digital Age by Simplifying It”, released by the Regulatory Transparency Project of the Federalist Society, October 27, 2017 (https://rtp.fedsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/RTP-Intellectual-Property-Working-Group-Paper-Copyright.pdf).

Executive Summary

Copyright laws and regulations aren’t keeping pace with modern technological change, but not for the reasons some seem to think. The basics of copyright are fully compatible with modern technology, but specific provisions enacted years ago to try to address long-gone business and technological problems are still on the books. Instead of solving yesterday’s problems, these sticky laws shackle today’s creative marketplace.

One of the great frustrations of copyright law is that, as explained below, although the fundamental bases of copyright law remain sound and are more important than ever before in today’s information economy, the Copyright Act is a statute wrapped in insider jargon and layers upon layers of complexity that rival the Internal Revenue Code – reflecting the piecemeal way many provisions of the Copyright Act get enacted in reaction to specific problems of the day and often due to intensive lobbying by affected industries. These attempts, even if well-intentioned, to make the Copyright Act responsive to modern needs have left parts of copyright law frozen in time. Once enacted, outdated provisions have remained on the books even though the provision was meant to address problems that haven’t existed for a very long time, creating a variety of real-world problems.

Examples abound of “sticky” provisions of the Copyright Act that were enacted as reactions to technical problems but remain in force today. For example, one finds provisions providing a government-run framework for licensing performances by coin-operated jukeboxes, as well as technology specific provisions regulating the manufacture and distribution of digital audio tape machines. There is a provision regulating VHS and Beta format analog video cassette recorders and 8mm analog video camcorders. And there is a provision meant to swaddle and protect the once-infant internet industries of the late ‘90s –companies that today are among the largest in the world. One also finds provisions meant to foster emerging community antenna television systems and backyard satellite dishes – precursors to today’s large cable and satellite systems. The need for government intervention to address these problems of the 1990s, 1980s 1970s – and even as far back as the 1900s – has long since disappeared. In some cases, the evolution of technology has rendered these provisions at best obsolete and at worst harmful. In other cases, past assumptions by Congress that turned out to be mistaken resulted in adoption of provisions that are similarly unproductive. And in still others, the policy objectives of these provisions have long-since been achieved, often despite, not because of, complex copyright laws. Yet the laws remain in place as irrelevant and even obstructive vestiges of now-outdated policies.

While many of these examples seem humorous and even harmlessly quaint, there are provisions have since outlived their usefulness or otherwise become an impediment to the very creativity and innovation the copyright law is designed to foster. This paper will explore two such provisions: one related to the posting and hosting of infringing video and music content, and the other related to the retransmission of programming by satellite operators. These laws, when enacted were complex, opaque, chose winners and losers in the marketplace, and froze in place the business models and technology of the moment. Neither laws serve the goal of ensuring that incentives and protections remain strong so creativity and innovation can flourish. In this age of rapid innovation and change in the way movies, music, books, journalism, software and other cultural and innovative works are created and consumed, it is important to have laws that are general-purpose, transparent, and market-based, allowing people now and in the future the freedom to decide and negotiate new uses of creative works.

Copyright law plays an essential role in American cultural and technological leadership. By getting the government out of the business of setting the terms and conditions for cable and satellite retransmission of broadcast television and by revitalizing the DMCA, Congress could enable creators to further invest and experiment with new content and distribution models, and spend more time and resources composing new works – to the benefit of consumers, creators and the strength of our cultural and creative economy.

I. Background on U.S. Copyright Law

The Framers of the U.S. Constitution understood the importance of strong legal protection for intellectual property (IP). At the urging of George Washington and James Madison, the First Congress enacted a copyright law in 1790, which was strengthened by subsequent Congresses and cited favorably by the courts in the early decades of the American Republic.1 Copyright has been a central feature of American intellectual property law since that time, incentivizing authors, musicians, and other creators to produce new works by enabling them to sustain themselves from the fruits of their labor, unencumbered by government.

The U.S. Copyright Office defines a copyrighted work as follows: “Copyright is a form of protection grounded in the U.S. Constitution and granted by law for original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression…including literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, such as poetry, novels, movies, songs, computer software, and architecture.”2

The U.S. Department of Commerce recently confirmed the key role copyright and other IP-based industries play in American economic success:

Patents, trademarks, and copyrights are the principal means for establishing ownership rights to inventions and ideas, and provide a legal foundation by which intangible ideas and creations generate tangible benefits to businesses and employees. IP protection affects commerce throughout the economy by: providing incentives to invent and create; protecting innovators from unauthorized copying; facilitating vertical specialization in technology markets; creating a platform for financial investments in innovation; supporting startup liquidity and growth through mergers, acquisitions, and IPOs; making licensing-based technology business models possible; and, enabling a more efficient market for technology transfer and trading in technology and ideas.3

This Commerce Department study4 found that copyright and other IP-based industries directly accounted for 27.9 million jobs in 2014, up 0.8 million from 2010, with copyright-intensive industries supplying 5.6 million jobs (compared to 5.1 million in 2010). Furthermore, private wage and salary workers in IP-intensive industries earn significantly more than those in non-IP-intensive industries, with the wage premium having grown over time from 22 percent in 1990 to 42 percent in 2010 and 46 percent in 2014. In addition, and very significantly, the U.S. value added by IP-intensive industries increased substantially in both total amount (from $5.06 trillion to $6.6 trillion) and GDP share (from 34.8 percent to 38.2 percent) between 2010 and 2014.

Copyright has been a central feature of American intellectual property law since that time, incentivizing authors, musicians, and other creators to produce new works by enabling them to sustain themselves from the fruits of their labor, unencumbered by government.

II. Large Scale Theft of Copyrighted Works Chills Creativity and Innovation

Keeping the copyright law up to date are vitally important to the US economy. Copyrighted intangible products are successfully being marketed to consumers through digital distribution technologies such as download and streaming services through for-profit contractual transactions in the marketplace, much as tangible goods and services are marketed. These products and services, which have conferred enormous new benefits on consumers, have proliferated by virtue of flexible contractual agreements between willing buyers and sellers – underpinned by strong copyright protections that allow rights in creative works to be clearly defined and for markets to develop around them.

That vibrant creative marketplace, however, is threatened by the persistent and growing problem of online theft facilitated by digital technologies. For instance, according to the Music Industry Coalition, between 2001 and 2015 music industry revenues fell from $14 billion to $7 billion – losses attributed significantly to piracy.5 And according to a 2012 survey of academic literature contemplating the effects of piracy, Carnegie Mellon University researchers concluded “The vast majority of the literature (particularly the literature published in top peer reviewed journals) finds evidence that piracy harms media sales.”6

What’s more, piracy isn’t just a problem for content creators – it’s also a concern for innovative new online distribution services. In a 2015 letter to shareholders, Netflix stated, “Piracy continues to be one of our biggest competitors. [Its] sharp rise relative to Netflix and HBO in the Netherlands, for example, is sobering.”7 Similarly, Spotify has noted that piracy is its greatest challenge in Asia.8

In the early days of the internet, Congress enacted the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA) to promote a robust digital economy by providing meaningful protection for creative works made available in digital form while also protecting legitimate online services against unreasonable liability for infringing activities of their users.9 The law was intended to encourage rights holders and legitimate online service providers to work together to find solutions to online theft. Its basic construct was designed to preserve incentives for cooperation and shared responsibility, protecting good-faith intermediaries against unreasonable liability for the actions of their users while ensuring meaningful accountability for bad actors who knowingly facilitate infringement or who build businesses based on the theft of intellectual property.10 But creators have argued that the law has failed to live up to its promise and objective, shifting the burden entirely to copyright owners while encouraging online intermediaries to do the bare minimum required to avoid liability, providing broad protection to bad actors for whom protection was never intended. Thus, for purposes of the DMCA, the line between innocent intermediaries and infringing businesses has all but been erased as a practical matter, and notice and takedown has degenerated into an endless game of “Whack-a-Mole” as infringing material reappears online almost immediately after it is taken down.

The scale of the problem is immense. Google’s Transparency Report reveals that in 2016 Google alone received well over 900 million takedown requests.11 For a single site (thepiratebay.se), Google received 4.21 million takedown requests (over 900 per week) between February 1, 2012, and March 9, 2017. A 2013 paper by Marquette Professor Bruce Boyden showed that in the six months ending in August 2013, the six major Hollywood studios collectively sent over 25 million takedown notices.12 In a 2016 filing with the U.S. Copyright Office, the Motion Picture Association of America highlighted specific examples of the scope of the “Whack-a-Mole” problem, including the fact that Disney sent 34,970 takedown notices for illegal copies of Avengers: Age of Ultron at a single site (Uploaded.net) in a three-month period, an average of more than 375 notices a day.13 NBC Universal sent even more (58,246) for Furious 7 to a single site, averaging nearly 650 notices a day to one site.14

While current federal law provides a variety of legal and government tools to combat online infringement, such as civil lawsuits and enforcement actions by the Department of Homeland Security or the Department of Justice, they are time consuming, expensive and, in many cases, futile. The notorious file sharing service provider LimeWire operated for more than 10 years and was estimated to have been installed on a third of all computers worldwide before finally being shut down and agreeing to pay $105 million in damages after five years of litigation with the music industry.15 Megaupload operated for five years as one of the largest repositories for infringing content, amassing more than 150 million registered users, causing more than half a billion dollars in economic harm to copyright owners, and reportedly accounting for four percent of all the traffic on the internet before being taken down by the U.S. Department of Justice.16 Five years later the lead defendant in that case is still fighting extradition to the United States. The infamous piratebay website continues to operate with impunity notwithstanding its founders having been convicted of criminal copyright infringement and sentenced to prison.17

Recognizing the law’s shortcomings, internet services and content owners have worked to implement voluntary solutions. For example, in 2011, the five largest internet service providers and rights holders implemented a “Copyright Alert System,”18 dealing largely with casual users of P2P networks and educating consumers about infringing behavior. That program completed in 2017, but content owners have worked to strengthen voluntary initiatives and best practices with payment processors,19 ad networks and advertisers,20 and online registries.21

Creators also continue to make their content available to consumers in new ways. For instance, the Motion Picture Association of America reports that its members make their movies and television shows available on over 114 legal online distribution platforms. Similarly, more than 360 music sites are serviced by record labels worldwide, licensing over 40 million sound recordings.22 And digital books, and other creative works are ubiquitous. However, these services still face the difficult task of competing with “free.” For example, while HBO makes “Game of Thrones” available online worldwide at the same time it airs on pay-TV, it was still the most pirated show in the world in 2016 – a dubious honor it’s enjoyed for five years running.23

There is no silver bullet solution. Curtailing online infringement will require a combination of effective laws, robust enforcement, and private sector cooperation. These are, however, imperfect solutions if not buttressed by a modern legal framework for the digital age that fosters cooperative efforts and a fair and healthy market for copyrighted works.

Thus, for purposes of the DMCA, the line between innocent intermediaries and infringing businesses has all but been erased as a practical matter, and notice and takedown has degenerated into an endless game of “Whack-a-Mole” as infringing material reappears online almost immediately after it is taken down.

III. The Corruption of the DMCA’s Notice-and-Takedown System

In 1998, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) was signed into law.24 Recognizing both the opportunity and challenges of technological advances online, the DMCA sought a balance between ensuring protection for copyright owners and creating an environment for continued growth and development by online service providers. Unfortunately, nineteen years later, the DMCA has failed to live up to its original intent, providing increasingly broad application of limitations on liability for service providers while simultaneously decreasing the effectiveness of protection for copyrighted works. Many factors have contributed to the need to update this antiquated law.

A. Basic Background on the DMCA § 512 Notice-and-Takedown System

As the internet grew in the late 1990s, copyright owners became increasingly concerned that their works were appearing online without their authorization. As complaints increased, internet service providers (ISPs) found that such unauthorized works on their system created potential liability for them. In 1998, Congress passed (and President Clinton signed) the DMCA as a compromise, intending an enforcement system for copyright owners and a predictable online business environment for responsible ISPs.25

Reflecting the sentiment of a Department of Commerce White Paper26 and court cases, Congress declined to provide service providers with blanket immunity from liability (which the DOC felt “would encourage intentional and willful ignorance”).27 Congress similarly declined to adopt the ISPs’ preferred solution, which would have made the sole condition of liability protection for ISPs the removal of infringing content upon notice from a copyright owner.28 Instead, Congress adopted a framework of shared responsibility and stated that it sought to “preserve strong incentives for service providers and copyright owners to cooperate to detect and deal with copyright infringements that take place in the digital networked environment.”29 It did so through a framework that seeks to protect good-faith intermediaries from unreasonable liability based on the infringing acts of their users while at the same time withholding protection from bad actors who knowingly and materially contribute to infringement or who build businesses on infringement that they are in a position to control. Therefore, with Section 512 of the DMCA, Congress offered ISPs limited liability protection (a “safe harbor”), conditioned not only on the ISP expeditiously taking down infringing content through a “notice and takedown system,” but also on the ISP taking swift action in response to known infringing conduct and on its taking steps to to curtail infringements that it can control and from which it directly benefits. The safe harbor is also conditioned on the ISP identifying a contact to receive infringement notices, adopting a policy for the termination of repeat infringers where appropriate, and accommodating and not interfering with standardized measures for protecting copyrighted works. Where content is removed in response to a notice and the user who posted the content believes it was wrongfully removed, the user can file a counter-notice to the ISP, at which point the ISPs must reinstate the content unless the copyright owner files a court action to keep the content down.

B. The DMCA Doesn’t Work Today

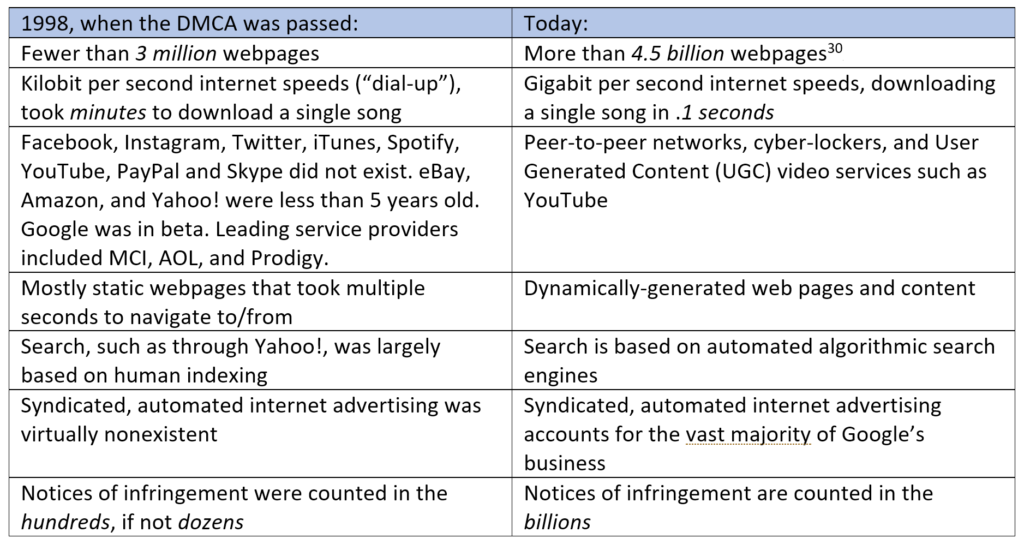

Of course, the DMCA was written nearly two decades ago (ancient history in the internet age), when internet speed was “dial-up.” The ISPs of the day were services such as MCI, AOL, and Prodigy, and content was largely found on static web pages, easily removed and not routinely replaced. This is a far cry from the internet of today, and Congress could never have anticipated how quickly platforms – and technology itself – have changed. Consider:

The unfortunate result is a system built for an earlier time that no longer functions properly in today’s online world. Its obsolescence is compounded by the many court decisions construing the law in a way that has narrowed it to little more than a notice-and-takedown-only statute that provides immunity for compliance with a formality and without regard for knowledge and intent. That is not the law Congress enacted. Yet, as currently applied, services based on infringement can comply with notice and takedown, benefit from the safe harbors, and still be assured that the infringing material that feeds their business will remain openly available on their site. Today, the law provides protection to the kinds of bad actors Congress sought to exclude. As a result, to try to keep up with the volume of infringements, creators must spend millions of dollars to monitor online platforms themselves — money (and time) that could be better spent creating new works. Grammy Award-winning composer Maria Schneider captured the frustration and despair of the creative community well in congressional testimony, saying:

The majority of my time is now spent simply trying to protect my work online, and only a small fraction of my time is now available for the creation of music. So instead of the Copyright Act providing an incentive to create, it provides a disincentive.31

Even when a noticed infringement is taken down, it is put right back up. In fact, many sites have engineered their system to repopulate these infringements automatically, leading to the never-ending game of “Whack-a-Mole”. Many have simply developed “bots” that automatically repost content within seconds. Thus, a key purpose of the DMCA – to get illegal copies offline – is wholly ineffective. IFPI has reported that 94 percent of all takedown requests they sent in 2015 related to recordings uploaded repeatedly to sites already notified that the content was infringing.32

And when used, technological measures to prevent infringements aren’t as effective as they could be. For instance, while YouTube has touted its Content ID technology as a means of weeding out infringing files, many content owners have reported publicly on its significant shortcomings. Following the release of Taylor Swift’s “1989” through March 11, 2016, Universal Music Group sent approximately 20,000 manual takedowns in addition to the nearly 114,000 Content ID blocks.33 Assuming each manual view/takedown took only one minute to generate (a likely gross underestimate), that’s 333 hours (about two months of work) for one person regarding one artist’s album on one platform. Sony Music Entertainment also identified and claimed or blocked almost 1.9 million videos since December 2012 that incorporate Sony recordings but were not identified by Content ID.34 This does not depict a technological measure that is effective in dealing with infringement in any meaningful way.

Beyond the technological aspect, however, the problems with the DMCA today arise from the way it is being used – and abused. In the worst cases, websites and services are operating businesses based purely on infringement and consider responding to takedown notices as a nuisance that is merely a cost of doing business. These pirate sites and services continue to operate with the assistance (whether intentional or not) of ISPs and other intermediaries that are also provided with the DMCA’s immunity – a safe harbor within a safe harbor. Obviously, the DMCA was never intended as a free pass for such illicit sites and services, but current applications of the law routinely fail to distinguish between such pirates and the true good-faith, passive ISP conduits originally intended.

Of course, given the wide application (and reading) of the DMCA’s safe harbors, even legitimate sites reap benefits and generate costs that were never intended. Giant multi-billion dollar global internet companies that have built businesses on content distribution leverage the imbalance created by the out-of-date law to distort the free market and obtain artificially low rates for copyrighted works. They threaten content creators with a Hobson’s Choice between a licensing deal at bargain basement rates for their work or unremedied mass piracy that flows from a broken system of notice-and-takedown and immunity.

C. Courts Decisions Have Further Enabled Abuse of the DMCA

The problems with outdated provisions of the DMCA have been manifested by court decisions, that although perhaps true to the letter of the law have strayed from the DMCA’s original intent and has in turn facilitated abuse by unintended beneficiaries.

1. Knowledge Standard

Congress intended that awareness of facts from which infringing activity was apparent – including “representative lists” of infringement at a particular site provided by copyright owners – would give rise to “red flag” knowledge for service providers, requiring action to remove or disable access to the infringing material. The relevant legislative history states that the DMCA safe harbor would be unavailable to an ISP where “… the copyright owner could show that the provider was aware of facts from which infringing activity was apparent,” including facts making it apparent “that the location was clearly… a ‘pirate’ site…”35 Similarly, the law provides that where there are many works infringed at the same site, the copyright owner may provide the ISP with a “representative list” of such infringements rather than requiring the copyright owner to catalog each and every infringement at that site as a condition to having access to those infringements blocked. Unfortunately, courts have effectively stripped the “red flag” test and the option of sending “representative lists” of infringements out of the DMCA by allowing service providers to ignore obvious widespread infringement, instead requiring copyright owners to inform services of every single instance of infringement (link by link, file by file), even if the service is aware of rampant piracy by its users and could easily identify and prevent similar infringements more effectively on its own.

Examples of this failure include the lawsuit brought against YouTube by Viacom,36 where in the face of evidence that YouTube’s founders were concerned that taking more aggressive action against widespread infringement would reduce traffic to the site by as much as 80 percent, the court stated that even though the jury “could find that the defendants . . . welcomed copyright-infringing material being placed on their website,” the “red flag” provision requires “knowledge of specific and identifiable infringements of particular items”; and Vimeo,37 where the court noted numerous “disconcerting” examples of Vimeo employees turning a blind eye to infringement, but refused to consider them on the ground that it was not particularized to the “specific instances of infringement at suit in the litigation.”

The unfortunate result of such decisions is that the “safe harbor” of the DMCA has led service providers to apply a willful ignorance, with bad actors running infringement-based businesses but still enjoying safe harbor protection through avoidance of knowledge of specific infringements, and good-faith intermediaries fearing proactive steps will imply knowledge of infringing behavior. Congress, in fact, intended not to “discourage the service provider from monitoring its service for infringing material”38 and quite explicitly anticipated that service providers would work with copyright owners to detect and deal with infringements on their systems.39 beneficiaries.

2. Benefit and Control

As enacted, the DMCA attempted to differentiate between bad actors and good-faith intermediaries by conditioning safe harbor protection on the service provider taking reasonable steps to stop those infringements they were in a position to control and from which they derived a direct financial benefit. This follows longstanding copyright law principles that hold third parties responsible for the failure to exercise their right and ability to control infringements that they benefit from directly. But courts have rendered the provision entirely hollow in the context of the DMCA.

Congress intended consideration of the service provider’s direct financial benefit which would “include any such fees where the value of the service lies in providing access to infringing material.”40 However, service providers’ direct financial benefit from access fees and advertising, using infringing material as a draw, are routinely allowed and disregarded. As the court in Perfect 1041 stated outright, “That an ISP hosts websites for a fee does not constitute direct financial benefit.” The court in Wolk v. Kodak42 also found for the defendant because his “profits are derived from the service they provide, not a particular infringement.”

Congress also intended consideration of the service provider’s right and ability to control the infringing material.43 Legislative history indicated that the law was intended “to preserve existing case law that examines all relevant aspects of the relationship between the primary and secondary infringer.”44 However, despite this guidance, the DMCA has been applied by courts to require “something more” than had been required under previous case law, including “something more” than the ability to remove infringing content or block access by infringing users. The bar now seems to be set unreasonably high, such that the requirement of this DMCA provision is now all but illusory, with only one court in the country finding it to be met in the last 15 years.45 This despite the fact that many service providers have complete control of their users’ activity, as evidenced by their terms of service, algorithmic tinkering in their own self-interest, and removing content from their systems on the basis of viewpoint-specific discrimination.46 Yet, they freely fail to apply such oversight when it comes to infringing activity. For example, according to the district court in Mavrix,47 the fact that all posts had to be approved and posted by a moderator before becoming visible on the site does not disqualify defendant from safe harbor protection. According to the court in Viacom, “knowledge of the prevalence of infringing activity, and welcoming it, does not itself forfeit the safe harbor,” and the decision by YouTube to “place the burden on Viacom and other studios to search YouTube 24/7 for infringing clips,” even if done to profit from the infringement, “does not exclude it from the safe harbor.”48 Absent conduct amounting to “participation in, []or coercion of, user infringement activity,” the exercise of editorial judgment and control over content, decisions to enforce content-based rules in some areas (e.g., pornography) but not others (e.g., copyright), and decisions to withhold access to content protection tools from those who don’t enter into content licensing arrangements with the service provider, do not rise to the level of the “right and ability to control” infringement, even if done for YouTube’s own business advantage and “regardless of their motivation.”49

3. Repeat Infringer

Congress enacted a requirement for eligibility for the safe harbors that service providers must adopt and reasonably implement policies for terminating the accounts of subscribers who are repeat infringers. This was intended to create a realistic threat of losing access by those who repeatedly or flagrantly infringe.50 Legislative history states that “[T]hose who repeatedly or flagrantly abuse their access to the Internet through disrespect for the intellectual property rights of others should know that there is a realistic threat of losing that access….”51 However, many service providers have failed to live up to this requirements and courts have not consistently applied it. As a result, repeat infringers continue with impunity and rarely, if ever, lose access. For example, in Perfect 1052, the court found Giganews’ repeat infringer policy to be reasonable, even though the site had removed over 531 million infringements, but terminated only 46 accounts.

4. Fair Use

A 2013 District Court case found that “Congress was aware well prior to the passage of the DMCA that the Supreme Court had made clear that the burden of proof for a fair use defense rests on the accused infringer.”53 However, in the DMCA context, some courts have effectively shifted the fair use burden to plaintiffs and unjustifiably expanded the application of fair use generally. For example, the Ninth Circuit improperly stated that the DMCA “requires copyright holders to consider fair use before sending a takedown notification, and that failure to do so raises a triable issue as to whether the copyright holder formed a subjective good faith belief that the use was not authorized by law.”54

5. Technical Measures

Congress intended for “… voluntary, interindustry discussions to agree upon and implement the best technological solutions available…”55 However, service providers have failed to implement any effective technological solution or to convene to create an industry standard.

D. Resulting Problems

The failure of the DMCA as it is currently applied manifests itself in several ways.

1. Continued Policy

Copyright owners have no effective means of protecting their works online. It’s unjust and unfair not merely to permit the continued theft of creative works and the destruction of livelihoods and businesses in the creative sectors of our economy, but to facilitate this result through a federal statute. Many sites and services have made millions (collectively, billions) over the years by drawing advertising and subscription revenue from the infringing material on their systems. Pursuing these bad actors takes years and significant resources, as they continue to operate under the veneer of legality under the DMCA. For example, German hacker Kim Dotcom built a multi-million dollar empire through his MegaUpload locker service, a repository of infringing-works made possible by the ineffective DMCA notice and takedown system.

2. Discount License

Services such as YouTube can take advantage of the DMCA’s safe harbor to offer unauthorized content to their customers and evade liability for the copyrighted works uploaded by users. As a result, they don’t need to take a license for the works they distribute, or they can take a license but demand bargain basement terms by threatening to relegate copyright owners to the futility of the notice and takedown process. This taints the entire marketplace and inevitably produces a race to the bottom for all licenses.

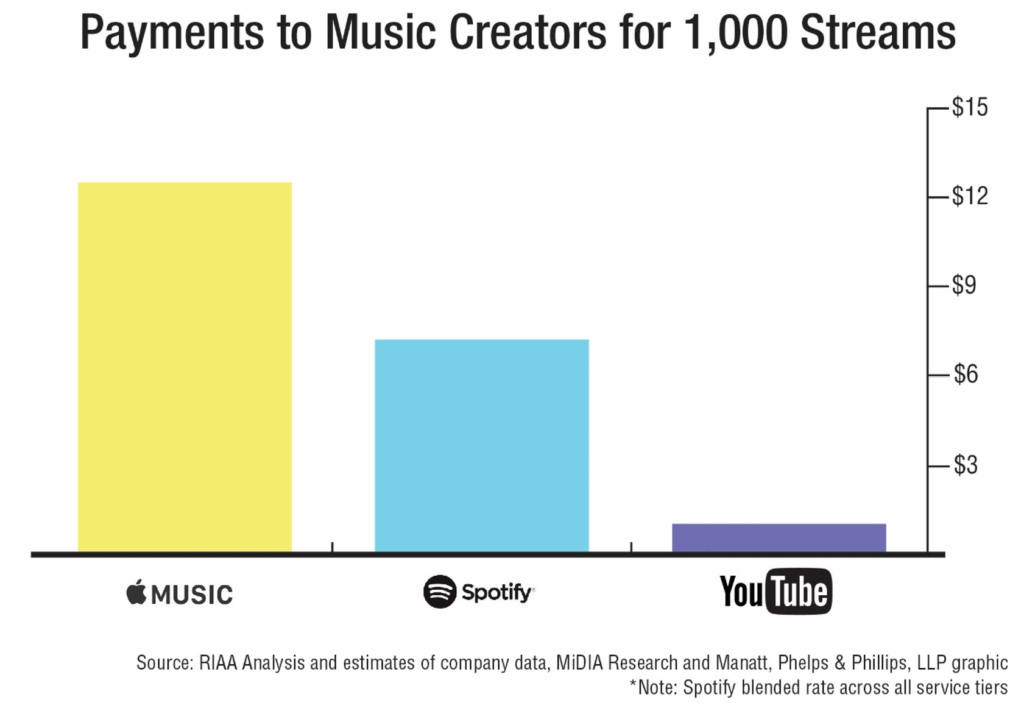

The effect of this can be seen clearly by looking at the facts from the music industry:

One thousand on-demand audio streams on a service like Spotify earns $7 for music creators, while the same number of streams on YouTube, which relies on the DMCA’s safe harbor, earns only $1. In fact, a March 2017 Phoenix Center study found that “DMCA safe harbor exploitation on services like YouTube costs the U.S music industry between $650 million to over one billion dollars a year in lost revenues.”56

3. Threat to Legitimate Services

The pirate sites that hide behind the DMCA and sites that offer a choice between discount licenses or an ineffective notice and takedown process both threaten the success of legitimate services. There is a competitive disadvantage between services such as Spotify (which takes market-based licenses) and services like YouTube (which can choose not to take a license at all, or take one only on terms it finds acceptable) because YouTube exploits the protections of the DMCA safe harbor.

4. Devalued Works

In addition to hindering their ability to make a living by devaluing the product of their hard work, the ineffective DMCA strips creators of control over their works. The rights provided by copyright law include the right to refuse licenses for uses of the work to which the author objects and/or would harm their reputation. For example, refusing to license music or popular fictional characters for use in extremist videos. The ineffectiveness of the DMCA as a tool to prevent such unauthorized uses goes beyond economic harm.

5. Threat to Creativity

Artists, songwriters, filmmakers, authors, labels, studios and others must spend their time and money searching for infringements instead of creating. If they can’t protect their works and make a return on their investment, they can’t afford to keep creating. And this affects no one more than the next generation of creators. This is not about protecting old, out-of-date professions – being an artistic creator is not an out-of-date job – but about stopping professional thieves.

E. Solutions to Consider

There are several ways to improve the DMCA so that it becomes the effective enforcement tool it was initially intended to be. First, courts could give back real meaning to the DMCA’s safe harbor conditions. This includes making “red flag” knowledge meaningful, requiring effective – and applied – repeat infringer policies, and taking more seriously service providers’ benefit and control of infringing sites and services.

Second, service providers themselves could go a long way toward solving the problem by working more cooperatively with copyright owners to deal with infringements that are readily apparent, by ensuring that infringing material that is taken down stays down, and by working to make standard technical measures meaningful and effective. While much of the discussion regarding the DMCA focuses on the process of noticing and responding to infringement, preventing infringement in the first instance certainly makes a good deal of sense.

Third, it may also be appropriate to consider legislative reform to update the statute and give effect to its original intent, such as ensuring that the law does not protect those that knowingly profit from infringement and that “take down” means “stay down.” Clearly, Congress did not intend the DMCA to become a never-ending game of “Whack-a-Mole” and, unless courts and service providers address the problem themselves, it may be necessary for Congress to act by clarifying the statute.

The majority of my time is now spent simply trying to protect my work online, and only a small fraction of my time is now available for the creation of music. So instead of the Copyright Act providing an incentive to create, it provides a disincentive.31

Receive more great content like this

IV. Coerced Fees for Retransmission of Broadcast Content by Cable and Satellite Companies Set by Government Bureaucrats

While the DMCA is based on an era where the internet was a small but promising phenomenon, another part of the Copyright Act harkens even further back to the days of rabbit ear antennas on televisions. In an effort to ensure that small, struggling cable and satellite providers got a fair shake, the Copyright Act was amended to protect these nascent businesses. Today, these now giant companies have long been able to negotiate for themselves. Yet copyright law still imposes a complex regime that has government bureaucrats intervening on their behalf to dictate the prices they pay and how those payments get divvied up among program producers.

A. History of the Section 111 Cable Compulsory License

In the 1960s, the emergence of Community Antenna Television (CATV) services – the precursors to today’s cable industry – presented new challenges in the application of copyright and communications law to the distribution of copyrighted television programming. These nascent CATV services started by locating antennas on the hills above rural communities with poor broadcast television reception to receive the signals of over-the-air broadcast television stations, amplify those signals, and carry them via co-axial cables strung on utility poles to the homes of individual subscribers of the CATV service.

Broadcasters and copyright owners objected to the unauthorized retransmission of TV programs to paying subscribers, and courts and government agencies wrestled with the question of how to apply copyright law to these disputes. 57 At that point, the 1909 Copyright Act was in force, written in an era when radio was in its infancy and television had not even been invented. The Supreme Court first settled these disputes by drawing a line between the functions performed by a broadcaster (who the Court said “performed” a copyrighted work within the meaning of that term in the Copyright Act) and a viewer (who the Court said does not “perform” a work and therefore does not implicate the exclusive rights of a copyright owner), and finding that a CATV system “falls on the viewer’s side of the line.”58

The Supreme Court did not have the last word in these disputes, however, as the debate shifted over into Congress, with the issue of cable retransmission being the primary reason the effort to update the 1909 Copyright Act took some 20 years to reach its conclusion.

In 1976, Congress finally adopted its general revision of the copyright law, in significant part to reject the Supreme Court’s decisions in these disputes and to make clear that “a cable television system is performing when it retransmits a broadcast to its subscribers.”59 This decision followed the recommendation of the Register of Copyrights, stated as follows:

On balance, … we believe that what community antenna operators are doing represents a performance to the public of the copyright owner’s work. We believe not only that the performance results in a profit which in fairness the copyright owner should share, but also that, unless compensated, the performance can have damaging effects upon the value of the copyright.60

Thus, the 1976 Copyright Act defined a public performance broadly to include any act of “transmit[ing] or otherwise communicat[ing] a performance… of the work to… to the public, by means of any device or process.”61 At the same time that it amended the Copyright Act to make clear that cable operators must compensate copyright owners for the retransmission of broadcast television programming, Congress adopted the section 111 cable compulsory license to ease the process of licensing such programming for cable operators.

The Supreme Court describes the section 111 license as “creat[ing] a complex, highly detailed compulsory licensing scheme that sets out the conditions, including the payment of compulsory fees, under which cable systems may retransmit broadcasts.”62 Congress chose such a complicated regulatory scheme for licensing the retransmission of broadcast programming by cable systems, rather than relying on the market to produce such licenses, based on the assumption “that it would be impractical and unduly burdensome to require every cable system to negotiate with every copyright owner whose work was retransmitted by a cable system.”63 This view reflects the fact that authorization to retransmit the signal of a broadcast station would require the authorization of the copyright owner in every copyrighted work performed or displayed via the broadcast transmission, including each individual program, and the music and other copyrighted works contained within those programs, and an assumption that the market was incapable of providing a mechanism for clearing those rights on such a scale.

Rather than require small and nascent cable systems to negotiate in the market for the rights to the programming they retransmitted, Congress created a system where cable systems could bypass program providers and obtain the necessary copyright licenses in the form of a statutory license directly from the government. Copyright owners would be compensated from a pool of royalties paid by cable systems at rates set by the government.

B. History of the Section 119 and 122 Satellite Compulsory Licenses

A dozen years after the enactment of the cable compulsory license, Congress again addressed the challenge of a young, emerging industry with what it described as an interim solution. The Satellite Home Viewers Act of 1988 was enacted to spur the growth of a start-up direct-to-home satellite industry as an effective competitor to cable. Congress determined “that the public interest best will be served by creating an interim statutory solution that will allow carriers of broadcast signals to serve home satellite antenna users until marketplace solutions to this problem can be developed.”64

Like the section 111 cable compulsory license, the section 119 satellite compulsory license allows satellite providers to bypass program providers to resell television programming at rates set by the government. Unlike the cable compulsory license, the section 119 “distant signal” license applies only to the retransmission of programming contained in certain broadcast transmissions to “unserved households” or, in other words, to households that are unable to receive a signal of sufficient quality (as defined by the statute and regulation) using an ordinary antenna.

The “unserved household” limitation stemmed from the fact that copyright owners typically license their programming to local broadcasters on the basis of territorial exclusivity. A local broadcaster will negotiate for the exclusive right to broadcast a particular program in their market during the first-run broadcast window. Satellite technology in the 1980s did not allow for carriage of every station in every market or to limit retransmissions of those stations to viewers in those local markets. As a result, satellite providers would carry one or two local stations (e.g., New York and Los Angeles) for each television network (e.g., ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC) and transmit those stations’ signals to their subscribers in every market. The “unserved household” limitation was intended to limit the government’s abrogation of exclusive contracts that had been negotiated in local markets by operation of the statutorily compelled license to transmit broadcast programming from one station into another station’s market.

In adopting the section 119 license, Congress was clear that it “does not favor interference with workable marketplace relationships for the transfer of exhibition rights in programming,” and that by adopting a six-year sunset on the new satellite compulsory license it expected that “the marketplace and competition will eventually serve the needs of home satellite dish owners.”65 Yet rather than let the section 119 distant signal license sunset in 1994, Congress has continued to extend the license, in 1994, 1999, 2004, 2010, and 2014. And in 1999, as technology developed to enable satellite providers to target retransmissions to individual television markets, Congress added a new “local-into-local” satellite compulsory license to allow royalty-free retransmissions of television programming contained in a local station’s signal to subscribers of the satellite provider’s service in that local market. Unlike the section 119 distant signal satellite compulsory license, the section 122 local-into-local satellite compulsory license is not subject to a sunset date.

C. Marketplace Developments

The justifications that may have existed three and four decades ago for the statutory licenses no longer exist today. The objective of the satellite license has long since been met. Today, satellite services account for one-third of all multichannel video programming delivery (MVPD) subscribers and DirecTV and Dish Network are now, respectively, the second and third largest among all MVPDs.66 The concern underlying the cable license – that it is too cumbersome to negotiate the rights in the marketplace – no longer exists.

Since the adoption of the cable compulsory license, there has been an explosion in the competitive market for multichannel video programming. Today, cable and satellite services license programming for hundreds of non-broadcast networks directly in the marketplace, without the need for a compulsory license. Broadcast programming is also being licensed in arms-length transactions for video-on-demand on cable systems, for internet streaming and download, for transmission to mobile devices, and for other uses. The fact is, cable and satellite retransmission of broadcast stations is the only form of video distribution subject to government-set, compulsory distribution terms. And as the Copyright Office has repeatedly affirmed, cable and satellite rates set by the government are significantly below those that would have been negotiated in the market.67

There is no reason these rights cannot be negotiated in the market just as they are for every other form of video distribution, most of which carry some of the very same programming. For example, when cable and satellite providers retransmit the local Fox station’s broadcast of an episode of The Simpsons, the copyright terms and conditions for that retransmission, including the compensation paid by the cable or satellite operator to the producer of The Simpsons, is set by the government pursuant to the compulsory licenses. In many cases, that compensation is set at zero, regardless of what the free market might otherwise yield. But when the same episode airs on Fox’s FX Network and is retransmitted by the same cable and satellite providers, those copyright terms and conditions, including the compensation to the copyright owner, are determined by marketplace negotiations, without the involvement of the government. And when the same episode is made available for streaming over the internet via the FX Now app, those terms and conditions are also negotiated in the market.68 The 1970s-era notion that the marketplace cannot clear the rights necessary to enable retransmission of broadcast programming is misguided and anachronistic.

The Copyright Office came to this very conclusion as early as 1981, when the Register of Copyrights testified:

In the last five years, the cable industry has progressed from an infant industry to a vigorous, economically stable industry. Cable no longer needs the protective support of the compulsory license. A compulsory license mechanism is in derogation of the rights of authors and copyright owners. It should be utilized only if compelling reasons support its existence. Those reasons may have existed in 1976. They no longer do.69

For decades the Copyright Office has sounded the same theme. In a 2008 report, it found that both the cable and satellite industries “are no longer nascent entities in need of government subsidies through a statutory licensing system,” and they “have substantial market power and are able to negotiate private agreements with copyright owners.” The Copyright Office found that compulsory licenses “have interfered in the marketplace for programming and have unfairly lowered the rates paid to copyright owners,” and “[t]he time has come when private negotiations would serve the public interest, and interests of the creative community, better than either Section 111 or Section 119.” The report’s principal recommendation was “that Congress move toward abolishing Section 111 and Section 119 of the [Copyright] Act.” That recommendation mirrors findings in similar Copyright Office reports in 1997 and 1992, and a 1989 FCC report. The latest government report on this issue is a GAO report published in 2016, which supports the findings of the earlier Copyright Office and FCC reports that the compulsory licenses can be phased out and replaced with market-based licensing.70

Unfortunately, the reality has been that rather than being limited and phased-out, the satellite license has been renewed five times, most recently in 2014. With each renewal, the license has been expanded to place the government increasingly in the disfavored role of decision-maker with respect to exhibition rights in broadcast programming. Rather than serve the intended purpose of providing a sunset to temporary marketplace interference, the periodic renewal of the satellite license has proven to be a vehicle for the slow but steady expansion of the government’s incursion in an otherwise workable marketplace for multichannel video programming.

For example, rather than allow the satellite compulsory license to expire in 1999, Congress extended the license for an additional five years and added a new, permanent, royalty-free compulsory license for retransmission of the copyrighted programming on local broadcast stations into those stations’ markets.71 At the same time, it extended the old license to cover (for the first time) distant retransmission of programming aired on independent televisions stations (e.g., WGN) to commercial establishments, broadened the section 119 license to encompass satellite dishes on RVs and commercial trucks, and relaxed other safeguards for right holders. Congress also responded to lobbying by satellite providers and their subscribers for a rate reduction by slashing the “fair market” rate set in 1997, by 45 percent.72 It has taken twenty years of rate adjustments and cost-of-living increases for the rate to reach the level that was considered the “fair market” rate in 1997.73 The law now provides satellite services the right to retransmit all the copyrighted programming aired on broadcast stations each month for a mere 27 cents per-subscriber. They pay more than that for the postage when they bill their subscribers.

With repeated statutory renewals of the satellite compulsory license has come an ever-expanding list of “special exceptions,” allowing satellite carriers to import out-of-market stations to specific markets in order to serve certain special interests, without the authorization of the copyright owner or the local station that has negotiated with the copyright owner for territorial exclusivity. These special interests are obscured through nearly indecipherable language in the statute. For example, the statute includes a “special exception” to allow satellite providers to import out-of-market stations from within Oregon to households in certain counties that identify with a neighboring state’s local market (e.g., parts of eastern Oregon are served by the Boise ID media market). But nowhere in the statute do you find Oregon listed as the beneficiary of a “special exception.” Instead, the “special exception” applies to:

that State in which are located 4 counties that –

(i) on January 1, 2004, were in local markets principally comprised of counties in another State, and

(ii) had a combined total of 41,340 television households, according to the U.S. Television Household Estimates by Nielsen Media Research for 2004.74

Of course, only a single state could meet such a strange and narrow definition – in this case that state is Oregon. It is perhaps unsurprising that these market-specific “special exceptions” apply to markets in states like Oregon, Mississippi, New Hampshire and Vermont, whose Senators served in Senate Leadership or on the Senate Commerce Committee with jurisdiction over the renewal of the compulsory license. And however desirable or sensible the outcome may (or may not) be from the standpoint of the satellite carrier, the viewer, or the incumbent legislators, the fact is that these are arrangements that could be made through marketplace negotiations, yet they are instead being dictated by government.

Even the marketplace protections included in the statute are simply ignored. One satellite provider was found to have repeatedly flaunted the law’s prohibition on retransmitting distant market stations to subscribers otherwise capable of receiving the signals of the local broadcast stations, facing repeated court-ordered injunctions requiring it to terminate service to ineligible subscribers.75 Yet rather than fixing the problem, Congress has repeatedly grandfathered these subscribers, choosing to expand steadily the law’s interference with bargained-for exclusivity rather than face the political consequences of allowing those subscribers to lose out-of-market signals that were being improperly provided to them. Even after this same satellite provider was permanently enjoined from retransmitting distant signals anywhere in the country as a result of its willful and repeated violation of the law by retransmitting Los Angeles and New York stations to thousands of ineligible subscribers, Congress waived the injunction and restored its compulsory license in exchange for a promise to further a congressional policy objective by expanding its local-into-local service to markets nationwide.76

D. Resulting Problems

The cable and satellite compulsory licenses have long since outlived their usefulness. The licenses skew the market as copyright owners receive below-market rates dictated by government bureaucrats, and the marketplace remains burdened by significant unnecessary government intervention. According to the Copyright Office, evidence “supports the long-held view that the distant signal licenses have interfered in the marketplace for programming and have unfairly lowered the rates paid to copyright owners.”77 Such interference undercuts the public interest in continued investment in production of over-the-air broadcast television programming, which today can cost millions of dollars per episode to produce. This threat is only amplified by the fact that non-broadcast programming can compete for investment based on higher market-based rates paid for cable and satellite retransmission of non-broadcast stations.

The same Copyright Office report notes that while “below-market rates may have been justifiable when cable and satellite were nascent industries, … the current multichannel video distribution marketplace is robust and has, for a long time, overshadowed the broadcast industry.”78 For example, today Charter Communications has a market capitalization of approximately $100 billion, compared to CBS’s market capitalization of just around $25 billion. Comcast is large enough ($186 billion market cap) that in 2011 it acquired NBC and its parent company NBC Universal. There is simply no reason that the producers of copyrighted programming should continue to subsidize the operations of some of the largest telecommunications companies in America. As the Copyright Office has concluded, cable and satellite companies today “have the market power and bargaining strength to negotiate favorable program carriage agreements” and thus “the time has come when private negotiations would serve the public interest, and interests of the creative community, better than either Section 111 or Section 119.”79

Moreover, reliance on compulsory licenses has weighed down innovation in the marketplace for redistribution of broadcast television programming via new technologies and digital distribution platforms. In free market negotiations with copyright owners, non-broadcast channels have always acquired the rights necessary to sublicense retransmission by downstream cable, satellite, and other distributors. On the other hand, the Copyright Office notes, “[t]he current distant signal licenses have impeded the development of a sublicensing system” for broadcast programming because the copyright rights for cable and satellite retransmission of such programming have been cleared by the government (under the compulsory licenses) rather than in the market.80 As a result, broadcasters historically have not secured from copyright owners the rights to authorize further retransmission of the programming in their signal, since cable and satellite providers looked to the government for those rights rather than the broadcaster or the copyright owner.

The result has been that, as new distribution technologies emerged, broadcasters often found they lacked the copyright licenses necessary to authorize retransmission of their broadcasts in new media distribution channels. For example, the Copyright Office says it “is clear” that the cable compulsory license “is an anachronistic licensing scheme that cannot readily accommodate new types of services, such as [Internet Protocol], or changes in technology, such as digital television.”81 In the same way, whether dealing with efforts to enable satellite retransmission of television signals to airplanes or internet-based over-the-top television services, the result of years of having leaned on the crutch of compulsory licensing has been that it was difficult for broadcast channels to stand on their own in new markets. Consumers, copyright owners, and distributors have all been harmed by the delays caused in the pace of innovation as broadcast stations have had to renegotiate with copyright owners for the rights to sublicense retransmission of their signals before they were able to enter these new markets. Others that have not been subject to compulsory licenses have been better situated, since they have long been accustomed to acquiring broad rights to license further retransmission of their signals across different media. That has been changing, but the existence of compulsory licenses remains a drag on innovation in this space.

E. Solutions to Consider

For more than 25 years the Copyright Office has recommended phasing out these compulsory licenses. In 2010, Congress directed the Copyright Office to submit a report outlining proposals to achieve the phase-out and eventual repeal of the cable and satellite compulsory licenses. In its 2011 report, the Copyright Office advised that “Business models based on sublicensing, collective licensing and/or direct licensing are largely undeveloped in the broadcast retransmission context, but they are feasible alternatives to securing the public performance rights necessary to retransmit copyrighted content in many instances.”82 The Copyright Office went on to recommend that Congress adopt a date-certain for repeal of the distant signal licenses, with an appropriate transition phase to give adequate time for the market to develop workable alternatives, and that repeal of the local signal licenses occur at a later date. A 2016 congressionally-mandated GAO report examines the current licensing market and confirms the view that the compulsory licenses can be phased out and replaced with market-based licensing.83

Congress should follow these recommendations and transition to a market-based licensing system for the retransmission of broadcast programming by cable and satellite providers, similar to the one that now exists in the vibrant markets for cable and satellite of non-broadcast channels and for internet retransmission of both broadcast and non-broadcast channels. At a minimum, Congress should not extend further the distant signal satellite compulsory license when it sunsets in 2019.

In an effort to ensure that small, struggling cable and satellite providers got a fair shake, the Copyright Act was amended to protect these nascent businesses. Today, these now giant companies have long been able to negotiate for themselves. Yet copyright law still imposes a complex regime that has government bureaucrats intervening on their behalf to dictate the prices they pay and how those payments get divvied up among program producers.

V. Review of Solutions to Consider to Update Copyright for the Modern World

Fixing the DMCA Notice-and-Takedown System:

- Courts should more faithfully enforce the statutory conditions that must be met to qualify for the DMCA safe harbor protection from copyright liability, consistent with Congress’ intent that the law should promote cooperation and accountability in dealing with online infringement.

- Courts should give effect to (and stop ignoring) the DMCA’s provision that requires service providers to take action to block infringements at a site when provided with a representative list of infringements at that site, rather than allowing sites to tolerate widespread infringement while requiring copyright owners to engage in the Sisyphean task of identifying each and every infringing file as they appear on a site.

- Courts should apply the “red flag” awareness standard in the statute to prevent services that knowingly profit or build businesses around infringing activity from enjoying the benefits of the DMCA safe harbor.

- Courts should also weigh more seriously service providers’ benefit and ability to control or limit illegal activity on infringing sites and services in assessing safe harbor eligibility.

- Service providers should be incentivized to do their part to prevent infringement.

- Providers need to ensure that infringing material that is taken down stays down, and to work to make standard anti-infringement technical measures more meaningful and effective.

- Providers should give the intended effect to the “red flag” knowledge standard, taking reasonable steps to limit infringing activity they have reason to know is occurring on their sites without requiring copyright owners to send notices for every single infringing act occurring on the site.

- Providers should implement reasonable and effective repeat infringer policies.

- Publicly “naming and shaming” service providers that have been slow to deal with major infringements could incentivize providers to improve their practices and help foster an “infringement is bad” culture.

- Congress should consider amending the DMCA as necessary to ensure application of the safe harbor only to truly good-faith intermediaries, denying protections to intentional infringers and those who build businesses around infringement.

- To the extent courts and service providers fail to give effect to the DMCA’s objectives of accountability and shared responsibility, Congress should consider changes to achieve the desired balance.

- Such changes could include strengthening the DMCA’s “red flag” knowledge standard, providing a “takedown, stay down” requirement, clarifying the obligations to respond to representative lists of infringements at a single site, and strengthening the repeat infringer policy requirement.

- Congress should consider a variety of possible new measures such as, for example, enabling copyright holders to obtain disgorgement of service providers’ advertising and subscription revenues derived from the hosting of infringing content.

Fixing the Compulsory Licensing System for Cable & Satellite Broadcasts:

- Congress should eliminate the cable and satellite compulsory licenses.

- The U.S. Copyright Office has found that compulsory licenses have interfered in the market for programming and have unfairly lowered the rates paid to copyright holders.

- Congress should transition to a market licensing system by phasing out the cable and satellite compulsory licensing scheme, ending them by a date certain.

- At a minimum, Congress should not further extend the distant signal copyright license when it sunsets in 2019.

Footnotes

1 See generally Alden Abbott, “The Constitutionalist and Utilitarian Justifications for Strong U.S. Patent and Copyright Systems,” Heritage Foundation Legal Memorandum No. 179 (June 21, 2016), available at http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2016/06/the-constitutionalist-and-utilitarian-justifications-for-strong-us-patent-and-copyright-systems#_ftn17

2 “Copyright in General,” U.S. Copyright Office, available at https://www.copyright.gov/help/faq/faq-general.html#what

3 U.S. Department of Commerce, Press Release, “U.S. Department of Commerce Releases Updated Report Showing Intellectual Property-Intensive Industries Contribute $6.6 Trillion, 45.5 Million Jobs to U.S. Economy,” Sept. 26, 2016, available at https://www.commerce.gov/news/press-releases/2016/09/us-department-commerce-releases-updated-report-showing-intellectual

4 U.S. Department of Commerce, Intellectual Property and the U.S. Economy: 2016 Update (Sept. 2016), available at https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/IPandtheUSEconomySept2016.pdf

5 http://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2016/05/02/how-google-killed-the-music-industry-in-3-easy-diagrams/

6 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2132153

9 For a detailed discussion of the DMCA’s provisions, see U.S. Copyright Office, “The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998: U.S. Copyright Office Summary” (Dec. 1998), available at https://www.copyright.gov/legislation/dmca.pdf

10 See S. Rep. No. 105-190, at 40 (1998), “[The bill] preserves strong incentives for service providers and copyright owners to cooperate to detect and deal with copyright infringements that take place in the digital networked environment.”

11 https://www.google.com/transparencyreport/removals/copyright/#glance

12 http://cpip.gmu.edu/2013/12/05/the-failure-of-the-dmca-notice-and-takedown-system-2/

13 Id.

14 Id.

15 See http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/thr-esq/record-labels-settle-massive-limewire-188028

17 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/18/business/global/18pirate.html

18 See Center for Copyright Information, “The Copyright Alert System” (2016), available at http://www.copyrightinformation.org/the-copyright-alert-system/

19 See, e.g., http://www.iacc.org/online-initiatives/rogueblock

20 See, e.g., https://tagtoday.net/anti-piracy-program-application/, http://www.webpronews.com/white-house-iab-google-yahoo-microsoft-aol-launch-best-practices-to-fight-piracy-2013-07/, https://www.ana.net/content/show/id/23408

21 See, e.g., http://www.donuts.domains/donuts-media/press-releases/donuts-and-the-mpaa-establish-new-partnership-to-reduce-online-piracy

22 Investing In Music: The Value of Record Companies; International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) and Worldwide Independent Network (WIN); p.14; available at https://www.riaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ifpi-iim-report-2016.pdf

23 http://time.com/4618954/game-of-thrones-pirated-2016/

24 Pub. L. No. 105-304, 112 Stat. 2860 (Oct. 28, 1998).

25 S. Rep. No. 105-190, at 20 (1998).

26 “Intellectual Property and the National Information Infrastructure,” September 1995 (available at https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/com/doc/ipnii/ipnii.pdf).

27 Id at 122.

28 See National Information Infrastructure Copyright Protection Act of 1995, Hearing before the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Statement of William W. Burrington, May 7, 1996, S. Hrg. 104-849 at 38 (“[Copyright owners] must have the obligation to identify content that infringes their copyrights and to notify on-line service providers of copyright infringements. And service providers must remove the infringing material within a specified period of time or face liability.”).

29 S. Rep. No. 105-190, at 40 (1998).

30 http://www.worldwidewebsize.com, last visited 9/5/17.

32 IFPI Global Music Report (April 2016), page 23.

33 Universal Music Group’s filing dated April 1, 2016, in response to the request for written submissions issued by the U.S. Copyright Office, Docket No. 2015–7 (December 31, 2015).

34 Sony Music Entertainment’s filing dated February 21, 2017, in response to the request for additional comments issued by the U.S. Copyright Office, Docket No. 2015–7 (Nov. 8, 2016).

35 Report of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on S. 2037, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, S. Rep. No. 105-190 (1998).

36 Viacom Int’l, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc. 676 F.3d 19 (2d Cir. 2012).

37 Capitol Records, LLC v. Vimeo, LLC, 972 F. Supp. 2d 537 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

38 Conference Report on H.R. 2281, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, H.R. Rep. No. 105-796 (1998).

39 Report of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on S. 2037, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, S. Rep. No. 105-190 (1998).

40 17 U.S.C. §§ 512(c)(1)(B), 512(d)(2).

41 Perfect 10 v. CCBill, 488 F.3d 1102 (9th Cir. 2007).

42 840 F. Supp. 2d 724 (S.D.N.Y. 2012).

43 17 U.S.C. §§ 512(c)(1)(B), 512(d)(2).

44 Report of the House Committee on the Judiciary on H.R. 2281, the WIPO Copyright Treaties Implementation and On-Line Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act, H.R. Rep. No. 105-551, pt. 1 (1998).

45 See Perfect 10 v. Cybernet Ventures, 167 F. Supp. 2d 1114 (C.D. Cal. 2001).

47 Mavrix v. LiveJournal, 2014 WL 6450094 (C.D. Cal. 2014), reversed 2017 WL 4446029 (9th Cir. 2017). See also Viacom Int’l, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc. 676 F.3d 19 (2d Cir. 2012), UMG v. Shelter Capital, 718 F.3d 1006 (9th Cir. 2013), Hendrickson v. Amazon.com, 298 F. Supp. 2d 914 (C.D. Cal. 2003).

48 Viacom v. YouTube, 940 F. Supp. 2d 110 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

49 Id.

50 17 U.S.C. § 512(i).

51 Report of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on S. 2037, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, S. Rep. No. 105-190 (1998).

52 Perfect 10, Inc. v. Giganews, Inc., 993 F.Supp. 2nd 1192 (C.D. Cal. 2014).

53 Tuteur v. Crosley-Corcoran, 961 F. Supp. 2d 333 (D. Mass. 2013), citing Campbell v. Acuff Rose, 510 U.S. 569 (1994).

54 Lenz v. Universal Music Corp., 801 F.3d 1126, 1136-37 (9th Cir. 2015).

55 Id.

56 http://www.phoenix-center.org/PolicyBulletin/PCPB41PressReleaseFinal.pdf

57 See Fortnightly Corp. v. United Artists Television, Inc., 392 U.S. 390 (1968); Teleprompter Corp. v. Columbia Broadcasting, 415 U.S. 394 (1974).

58 See Fortnightly Corp, at 399.

59 See American Broadcasting Cos. v. Aereo, Inc., 134 S.Ct. 2498, at 2505-06 (2014) (quoting H.R. Rep. No. 94-1476, at 63).

60 Register’s Supplementary Report, Sec. 13(E)(6)(b) (1965)

61 17 U.S.C. 101.

62 See Aereo, 134 S. Ct. at 2506.

63 H.R. Rep. No. 1476, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., at 89 (1976).

64 H.R. Rep. No. 887 at 13.

65 Id. at 15.

66 See Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition in the Market for the Delivery of Video Programming, Eighteenth Annual Report of the FCC, FCC DA 17-71, MB Docket No. 16-247 (2017).

67 See Satellite Home Viewer Extension and Reauthorization Act Section 109 Report: A Report of the Register of Copyrights, June 2008, at 71 (“copyright owners are under-compensated for the use of their works under the distant signal licenses. Only if Section 111 and Section 119 were repealed would copyright owners be able to realize the true worth of their programming.”); Satellite Home Viewer Extension and Reauthorization Act Section 110 Report: A Report of the Register of Copyrights, February 2006, at vi (“current statutory rates do not reflect fair market value.”); A Review of the Licensing Regimes Covering Retransmission of Broadcast Signals: A Report of the Register of Copyrights, August 1, 1997 (“no justification for the amounts paid to authors to be less than the fair market value of their works.”).

68 FX Now is a “TV Everywhere” app for computers, mobile devices, set top boxes (e.g., AppleTV or Roku), game consoles and smart TVs. It is made available to users who are authenticated as subscribers of participating cable and satellite providers, pursuant to agreements between those providers and Fox. See http://www.fox.com/fox-now

69 Copyright/Cable Television: Hearings on H.R. 1805, H.R. 2007, H.R. 2108, H.R. 3528, H.R. 3530, H.R. 3560, H.R. 3940, H.R. 5870, and H.R. 5949 Before the Subcommittee On Courts, Civil Liberties, and the Administration of Justice, 97th Cong., 959-960 (1981) (statement of David Ladd, Register of Copyrights, U.S. Copyright Office).

70 See Statutory Copyright Licenses: A Report to Congressional Committees, GAO 16-496 (May 2016).

71 This decision to circumvent the market is questionable given that satellite carriers are already at the table with local stations in negotiations pursuant to the Communications Act for retransmission consent rights (the right to retransmit the station’s signal, independent of the right to retransmit the copyrighted programming embodied in that signal). When Disney/ABC negotiates with a satellite carrier for carriage of its non-broadcast networks, (e.g., Disney Channel, Freeform, ESPN), it conveys the necessary copyright rights for retransmission of the programming on those networks, rights it obtains through direct negotiations with the copyright owners in that programming. But Disney does not need to obtain the same rights for cable or satellite retransmission of the programming on its broadcast stations, and it will not include such rights when it negotiates retransmission consent with cable or satellite carriers, since those rights are being conveyed by the government under the compulsory licenses. There is no reason to believe that free market negotiations for these rights couldn’t be handled in the same way they are for non-broadcast networks, among other possible market-based rights-clearing mechanisms. See Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act § 302 Report (2011) (available at https://www.copyright.gov/reports/section302-report.pdf).

72 In a 2006 Report the Copyright Office characterized this action as “Congress apparently abandon[ing] the policy goal of the 1988 and 1994 Acts of transitioning the satellite industry from statutory licensing of broadcast programming to marketplace licensing.” See Satellite Home Viewer Extension and Reauthorization Act § 110 Report, at 10 (2006) (available at https://www.copyright.gov/reports/satellite-report.pdf).

73 See Cost of Living Adjustment to Satellite Carrier Compulsory License Royalty Rates, 81 FR 84478 (Nov. 23, 2016).

74 17 U.S.C. § 122(a)(4)(C).

75 See CBS Broad., Inc. v. EchoStar Communs. Corp., 450 F.3d 505 (11th Cir. 2006).

76 See Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act of 2010, P.L. 111-175, 24 Stat. 1217, May 27, 2010.

77 Satellite Home Viewer Extension and Reauthorization Act Section 109 Report (2008).

78 Id.

79 Id.

80 See id.

81 Id.

82 Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act § 302 Report (2011) (available at https://www.copyright.gov/reports/section302-report.pdf).

83 Statutory Copyright Licenses: A Report to Congressional Committees, GAO 16-496 (May 2016).